Introduction

Posted on this website is a posthumous collection of the manuscripts of 龍思鶴 (pinyin: Lóng Sīhè). 龍思鶴 (photo in Figure 1), hereinafter referred to as “Lung See Hok” (which is an anglicization of his name that he had once used), was a Guangdong (廣東) or Yue (粵) Chinese (i.e. Cantonese Chinese) and a famous poet and calligrapher in the military-political sphere of China during the early years of the Republic. When he was young, he joined the revolutionary organization Tóngménghuì (同盟會) to assist in the revolutions led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙; better known among the Chinese as “孫中山”). He founded two newspapers of revolutionary thinking, namely, the Mínsūbào (民甦報; lit. People’s Awakening) and the Mínshēngbào (民聲報; lit. People’s Voice). He participated in some of the Yue Army’s (粵軍) military campaigns against Yuan Shikai (袁世凱) and the warlords in China. The majority of his works had used his own experiences as the theme. Thus, they are rich in both literary value and historical value. “Shuānqīngbái Zhāi” (雙清白齋; lit. The Study Room of Double Incorruptibility) was the name that he assigned to his study room. Hence, the posthumous collection of his manuscripts may be referred to as “Shuānqīngbái Zhāi Yígǎo” (雙清白齋遺稿 lit. a posthumous collection of manuscripts from the Study Room of Double Incorruptibility).

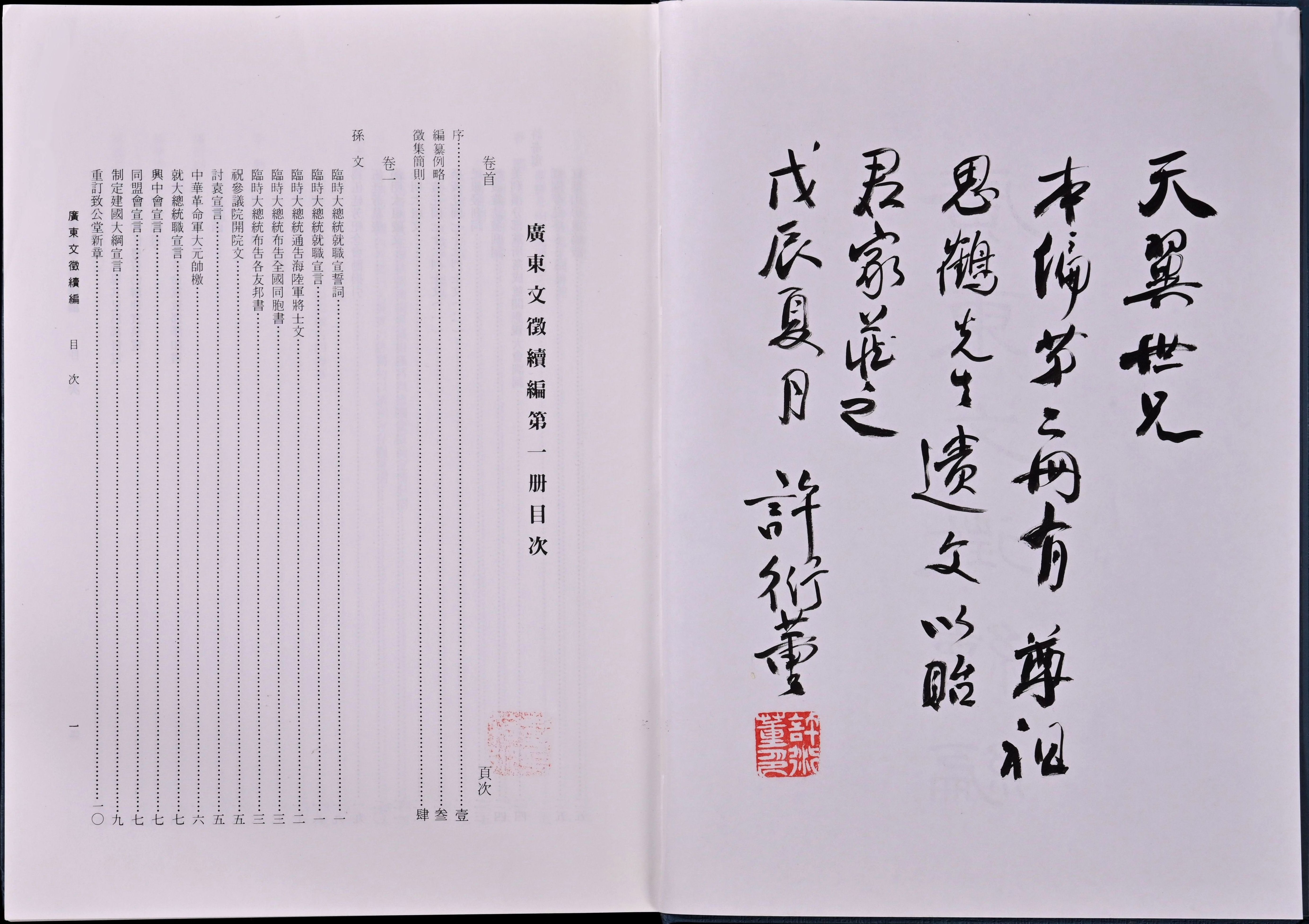

When Dr. Sun Yat-sen established a military government in Guangzhou (廣州), the provincial capital of Guangdong, to fight against the northern warlords, Lung served as a member of his aides. Furthermore, Lung headed the secretariat of the Yue Army when it was under the command of Xǔ Chóngzhì (許崇智). In his political career, Lung was appointed mayor from time to time for different counties in Guangdong including Qīngyuǎn (清遠), Gāoyāo (高要), Cháo’ān (潮安), Zēngchéng (增城), Huàxiàn (化縣), and Màomíng (茂名) and he earned people’s respect by being a caring, diligent, and incorruptible civil servant. A brief account of these events may be found in volume 2 of Guǎngdōng Wénzhēng Xùbiān (廣東文徵續編; lit. A Continuation of Assortment of Proses from Guangdong) edited by Xǔ Yǎndǒng (許衍董) et al (see Figure 2). After Dr. Sun’s passing in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who was originally the Yue Army’s chief of staff, succeeded in seizing power. Lung did not bow to the new boss but left the Yue Army for good. As a result, he was not assigned any influential position on the political stage of the Republic when the country was ruled by Chiang. During the second Sino-Japanese war, Lung lived in the then Portuguese colony of Macau for a period of time but later returned to mainland China. After the 1949 Revolution, he settled in the then British colony of Hong Kong until he passed away on the lunar new year day in 1955.

Lung See Hok had composed many literary works. Some of his manuscripts were lost even during his lifetime due to migration and the ravages of war. After his passing, his manuscripts were in the custody of his wife Liú Zhàoqióng (劉兆瓊), whose biézì (別字; lit. an official alternative given name) was Méiyíng (梅瑩). Liú had once lent the manuscripts to a group of her husband’s old friends and scholars to compile a memorial collection titled “Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí” (龍思鶴先生遺詩紀念集; lit. A Memorial Collection of Mr. Lung See Hok’s Poems). However, only a small number of Lung’s poems were selected for this publication and someone had taken the liberty to alter the relative order of the poems as well as edit some of the wording, such as changing from “Jiǎn cānmóuzhǎng” (蔣參謀長; lit. Chief of Staff Chiang) to “Jiǎnggōng Jièshí” (蔣公介石; lit. the revered Chiang Kai-shek). Some of the manuscripts might have also been lost during the process of compilation. After Liú passed away, Chan Yuet Lan (陳若蘭; pinyin: Chén Ruòlán), the wife of her eldest son, became the keeper of these manuscripts. Chan had once thought about publishing all of her father-in-law’s manuscripts but the project did not materialize since her father-in-law had two wives and many children, making it difficult for any daughter-in-law to take the liberty to act alone. In the fall of 2017, Chan’s younger daughter Lung Yuen Ying (龍愿凝; pinyin: Lóng Yuànníng) and son Lung Tin Yick (龍天翼; pinyin: Lóng Tiānyì) took over the role of manuscript keeper after deciding that their nonagenarian mother was too old to manage documents. They hired a professional photographer to photograph the manuscripts in preparation for posting on the Internet. Later on, Chan’s elder daughter Lung Mon Yin (龍夢凝; pinyin: Lóng Mèngníng), who had more free time than did her siblings since her physical location had exempted her from providing daily elderly care to her mother, offered to generate digitized transcripts for all manuscripts for the ease of reading and Internet search. By the end of 2021, the process of transcribing was still underway but the two sisters and brother had all lived past the age of 60 and they all had their medical problems. Hence, they decided to upload the transcripts and corresponding photos in stages, starting with the transcripts which had already been completed. Chan Yuet Lan was the eldest daughter of Chan Hon Yu (陳翰譽; pinyin: Chén Hànyù), whose biézì was Xīnyōng (欣庸) and who was a renowned general in the Yue Army when it was under the command of Xǔ Chóngzhì. Thus, the Lung sisters and brother are both in name and in fact descendants of the Yue Army.

There are thirty books of Lung See Hok’s extant manuscripts (see Table 1). They are all old-fashioned thread-bound notebooks. The writing was done by using a traditional Chinese ink-brush. The manuscripts can be broadly divided into two categories, namely, manuscripts of poems and manuscripts of proses. Manuscripts of poems amount to five sixths of the total collection. They were in different stages of editing and calligraphical scribing. Some of them had been neatly scribed, such as Yān Chén Jí (燕塵集). Some had been neatly scribed but subsequent changes were made on certain pages, such as Suì Hán Jí (歲寒集). Some were likely still in the process of compilation as suggested by their incomplete contents and missing manuscript titles, such as the manuscript marked with the Arabic number “22” on the righthand side of the front cover. Some might have been groups of first draft and later draft(s) kept together as can be seen from their identical titles, such as the three manuscripts bearing the same title “Héng Jiāng Jí” (橫江集). The manuscripts of proses were mainly written in semi-cursive script (行書) or cursive script (草書), including his own works and other authors’ works which he had recorded for perhaps the purpose of reference or critique. There is no sign that they had been meticulously organized.

It can be inferred from observation that Lung See Hok loved to use the calligraphical style known as Cuànbǎozǐ Bēi (爨寶子碑) to scribe his poetry works and the more words written in Cuànbǎozǐ Bēi script, the closer the draft was to what he would consider final. As for the other calligraphical styles of his, they each had a straight version and a slant version. Generally speaking, the slant version was used when he was writing faster. According to the handwriting identification by Lung Mon Ying, her grandmother’s handwriting may be found in a small number of the manuscripts. This should not be surprising since Liú was also educated and her husband might let her write a few lines for fun when re-scribing his own works. Furthermore, Lung had problems holding a pen with his right arm during his declining years due to hemiparesis; therefore, he could have asked his wife to lend a helping hand at times.

Upon a careful perusal of Lung See Hok’s manuscripts, we can tell that he had a theme in each manuscript of poems and he had organized his poems into different manuscripts according to the theme. The title of each manuscript can also be seen as related to the theme of the manuscript. For example, the theme of Hú Jīn Jí (湖襟集) was his tour of Xīhú (西湖), or West Lake, in Hangzhou (杭州); the theme of Tīng Cháo Jí (聽潮集) was his assignment as the mayor of Cháo’ān (潮安); and the theme of Jīn Xiè Jí (金屑集) was his gold (金) mining assignment in Ēnpíng (恩平). In addition to poems pertaining to the theme, a manuscript might also include poems written about other things occurred during the same period of time such as important news, social interactions, lived experiences, and reminiscences. Take Zài Qīng Jí (在清集) as an example, the theme was about his assignment as the mayor of Qīngyuǎn (清遠) but he also included a poem to celebrate his mother’s birthday as well as a poem about his marriage and family.

In terms of subject matters, Lung See Hok did not confine his poetry to any particular genre. He had composed poems that we may classify as narrative, lyrical, pastoral, reminiscent, satirical, intent disclosure, bidding farewell, or others. As for forms, he loved to adopt what Táng Dynasty (唐朝) poets had often used, such as lǜshī (律詩), juéjù (絶句), gǔfēng or gǔtǐshī (古風 or 古體詩), and yuèfǔ (樂府), with penta-syllabic jù (句; a jù is equivalent to a line in English poetry) or hepta-syllabic jù, but he seldom wrote in the form of a cípái (詞牌; lit. formation for writing poems in the cí category) which was popular in the Sòng Dynasty (宋朝). In his Zài Qīng Jí, there is a liánzhāngtǐ (聯章體; lit. a group of poems in identical forms under the same title) consisting of four poems written in the form of a forty-one-character cípái known as “Nǚguānzǐ” (女冠子) but this is a rare example. Regarding the aspect of narration, Lung might write about the same event at different times and put the different poems in different manuscripts. This is something that other poets might also do but such a practice is quite dissimilar to historiography in the form of biānniánshǐ (編年史; lit. annals) or in the form of jìshìběnmò tǐ (紀事本末體; lit. history presented in separate accounts of different events). Therefore, when we try to extract material from his poetry manuscripts for the study of history, it will be necessary to examine pertinent passages in the different manuscripts in search of complementary information. Sometimes, Lung might recount events with historical meaning in the preface to a poetry manuscript. He had actually reserved blank pages in the opening of some of his poetry manuscripts for this purpose but did not eventually follow through with writing all of the prefaces. Běi Zhēng Jí Zhīyī (北征集之一) is one example where he had written down the heading “Běi Zhēng Jízìxù” (北征集自序; lit. preface to Běi Zhēng Jí) in the first line of the first blank page.

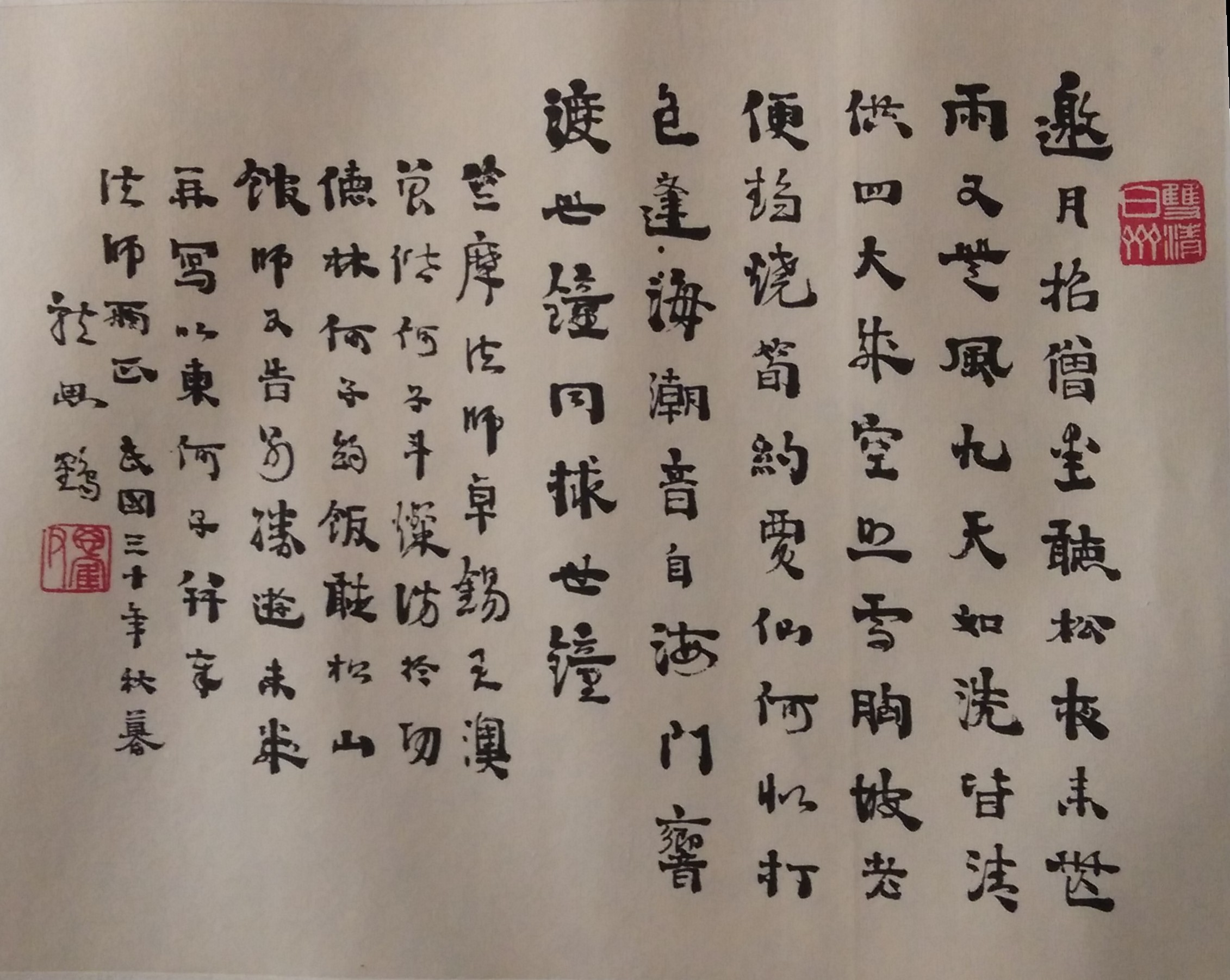

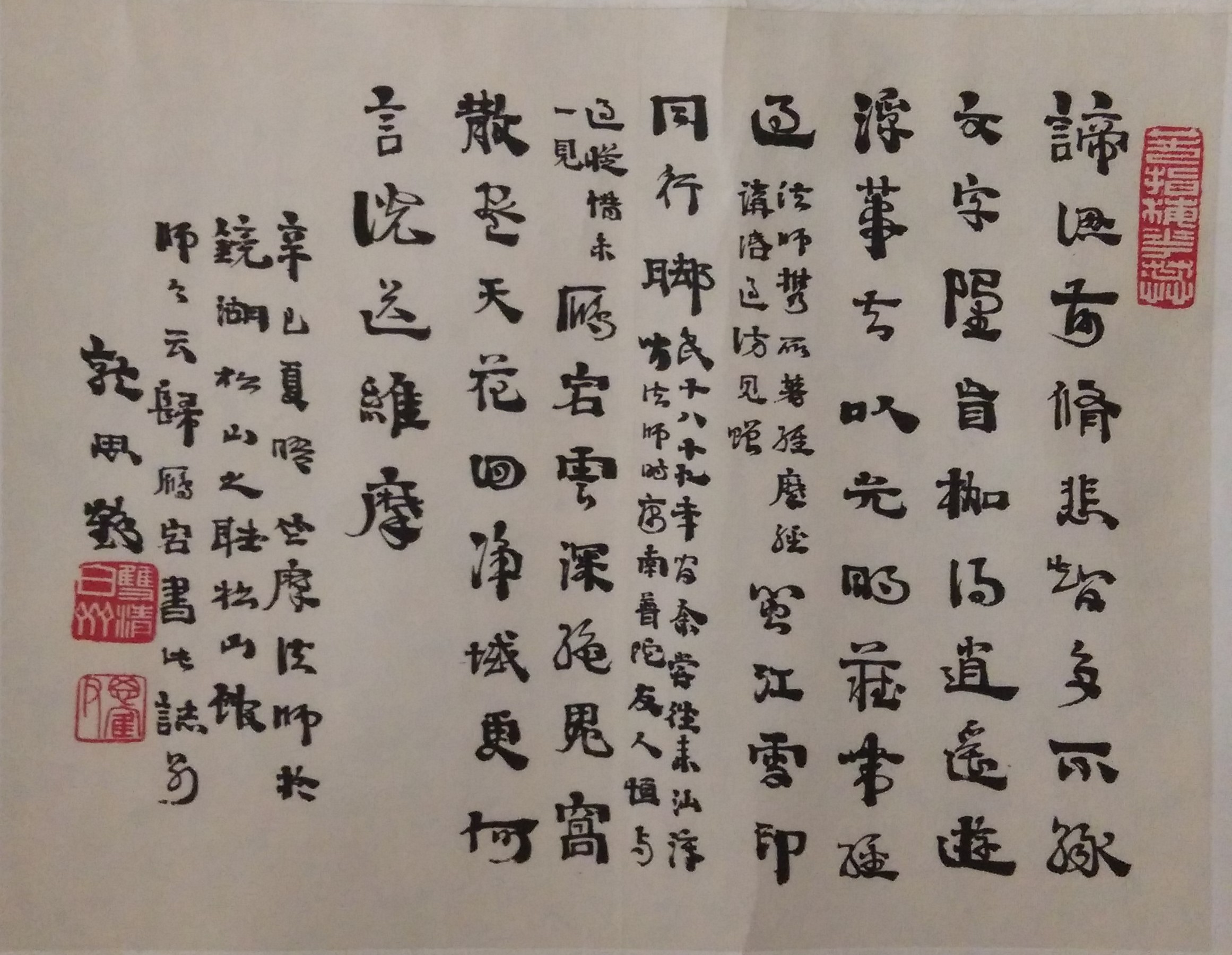

One thing to bear in mind when studying Lung See Hok’s manuscripts is that they are all handwritten drafts produced in a certain place at a certain time. Except for the factual information in his narrative poems, which is not variable, any poem found in these manuscripts is not necessarily the version that was published or sent to a friend during his lifetime or a creation that he had decided to not revisit for further refinement or re-scribing. For example, the poem titled “Fǎng Zhúmó Bùyù” (訪竺摩不遇) as written in his Táo Yǔ Jí (逃雨集) is identical to the version which has been circulating in the public domain for quite some time (ref. Wénhuà Zázhì (文化雜誌), Vol. 38, 1999, p. 69, published by the Instituto Cultural of Macau). However, two poems with the group title “Sòng Zhúmó Fǎshī Guī Yàndàng” (送竺摩法師歸雁宕) found in the same manuscript are partly different from the version he sent to Dharma Master Chuk Mor (竺摩法師; pinyin: Zhúmó Fǎshī) after further re-scribing. The version that he sent to Dharma Master Chuk Mor (Figure 3 and Figure 4) is preserved in the Chuk Mor Museum (竺摩文物館) at the Buddhist Triple Wisdom Hall (三慧講堂) in Penang, Malaysia. The museum version is smoother and more elegant in terms of both poetic skills and calligraphical skills when compared with the Táo Yǔ Jí version. This is usually the way that Chinese poets and Chinese calligraphers seek refinement in their creations, that is, to ruminate and re-ruminate, to scribe and re-scribe, and to ceaselessly pursue perfection.

Among the extant manuscripts of poems, twenty-three out of twenty-five have an Arabic number ink-brushed on the righthand side of the front cover. It may be difficult to ascertain the meaning of these Arabic numbers, which could have been added for the purpose of tallying at one point in time. By studying the front cover and contents of every manuscript closely, we can tell that these Arabic numbers do not necessarily represent the order in which the contents of the various manuscripts were composed or the order in which these manuscripts were compiled. We can also tell that they do not necessarily represent the order of occurrence of the time spans covered by the various manuscripts’ narrative poems. However, the photographer had followed the order of these Arabic numbers when doing his job and he did the manuscripts with Arabic number first before doing the ones without. In order to save time, no photos were taken for the back cover of a manuscript or any opposing recto and verso that are both blank. Yān Chén Jí (燕塵集), whose assigned Arabic number is “1”, was re-photographed once due to a technical problem and that part of the front cover on which the Arabic number was written had come off and was lost prior to re-photographing. Yě Shī Jí (野失集) was severely damaged during a household accident after Chan Yuet Lan emigrated overseas and it will require some painstaking efforts to restore it for photographing. As for manuscripts with an assigned Arabic number but without a title, the Arabic number will be used for identification purposes. For instance, the manuscript with a poem recounting Lung See Hok’s get-together with Liào Zhòngkǎi (廖仲愷) at a hot spring is referred to as “Book 5” because the manuscript is without a title but its assigned Arabic number is “5”.

When there is more than one manuscript with the same title, the current arrangement is to only upload photos and transcript of what appears to be the final draft unless there is a good reason for making an exception. In addition to photos of Lung See Hok’s manuscripts, photos of Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí are also included for the record. The photo file numbers displayed here are those automatically generated by the photographer’s camera. They have no special meaning in the context of this website. They are not necessarily consecutive because of the uploading of the best of two or more photos of any given cover or page or because of the re-shooting of missed pages. The photos are individually uploaded but the transcript of each manuscript is uploaded as a single PDF file. Photo file numbers are included in the transcripts for the ease of cross-reference.

One can learn a lot about Lung See Hok’s life story by reading his poetry manuscripts and the eulogies included in Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí. Lung See Hok’s original name was 龍寬焯 (pinyin: Lóng Kuānzhuō). His ancestral home was Shùndé (順德), Guangdong but the family had already settled in Nánhǎi (南海), Guangdong during his father’s generation. His mother Féng (馮氏) orally taught him Táng style poetry during his childhood. Thus, he was able to write Chinese poems when he was quite young. He had two wives and each wife had several kids. His first wife Lí (黎氏) conformed to the norms of the old society and stayed home to look after his mother. His second wife Liú (as mentioned above), who was married as a jiāntiāoqì (兼祧妻; i.e. a legally married wife who is recognized by the family as a daughter-in-law of the husband’s uncle rather than a daughter-in-law of the husband’s father and whose children will fulfil grandchildren’s obligations to both the husband’s father and the husband’s uncle), was a physician of western medicine with her own professional practice. Thus, she belonged to the group which led the way into a new era for Chinese women in the early years of the Republic. When Yuan Shikai proclaimed the Empire of China with himself as the emperor, Dr. Sun Yat-sen and his followers revolted against him in different parts of China. As part of that campaign, Lung went to Hong Kong to see his revolutionary friends in order to plan an attack on Yuan’s loyalist forces in the Shántóu (汕頭) area of Guangdong. For this he was arrested by a detective of the colonial government of Hong Kong. He was also deported and barred from entering Hong Kong for ten years after serving months of a jail term. This ordeal, as recorded in his Yān Chén Jí and Hú Jīn Jí, might have been the reason that he had stopped using the name Lóng Kuānzhuō after the deportation.

Perhaps due to his mother’s influence, Lung See Hok enjoyed chatting with Buddhist monks about the subject of chán (禪). Moreover, his revolutionary background enabled him to understand the importance of conducting institutional reform in Chinese Buddhism as proposed by the eminent Buddhist monk Tàixū (太虛). For these reasons, he treated Tàixū’s disciple Chuk Mor, who was also a poet, like an old friend in their first meeting and he took that opportunity to candidly express his view on such reform. The bits and pieces of this episode are traceable in his Táo Yǔ Jí. However, Lung’s friendship with religious people was not reserved for Buddhists. Many of his friends and relatives were Christians. He had attended numerous Christian rituals and Christian gatherings. He had also written several poems about Christianity. One of his sons with Liú was a Christian priest. Was his connection with Christianity driven by faith or by a desire to please his beloved wife Liú, who was a devout Christian? Well, he was the only person who knew the answer but a poem in his Táo Yǔ Jí titled “Yēsū Shèngdàn Suí Nèizǐ Zǎochū” (耶穌聖誕隨內子早出; lit. “Following My Wife to Go Out Early on Christmas Day”) might have given us a hint. Why did he, as the head of the household, use the word “suí” (隨; lit. following) to make it sound so passive? Why did he not use the word “dài” (帶; lit. bringing) to express a sense of self-initiative, or the word “xié” (偕; lit. together with) to show a sense of shared-interest? It is unlikely that a skillful writer would neglect such fine details.

If we compare Lung See Hok’s biographical data in his poetry manuscripts against pertinent data in the above stated Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí, it is not difficult to spot a discrepancy that may arouse curiosity. Lung stated in his Yān Chén Jí that he was twenty-five years old in the fifth year of the Republic. If this was the case, then his year of birth should be around 1891 CE and he died at an age of about 64. Why did his friends say that he died at the age of 74 when they wrote the article “Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Zhuīsīhuì Jì” (龍思鶴先生追思會記; lit. “Record of Mr. Lung See Hok’s Memorial Service”) for Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí? The difference of approximately 10 years cannot be explained by citing the Cantonese custom of adding three years to a deceased person’s age for the purpose of funeral decoration. Two possibilities may be considered for a plausible explanation. First, the age stated in his poetry manuscript was accurate but he had overstated it when he was young in order to make it easier to strive towards his revolutionary goals in the old society whose norms were to respect seniority and respect hierarchy; consequently, his real age was least known to people. Second, his friends were right but, after his jail term and deportation in Hong Kong during the anti-Yuan campaign, he had to conceal that identity in subsequent re-entrances so as to avoid further political persecution by the colonial government and he did it by using a biézì that was not previously known to the authority as well as an understated age; consequently, he became too used to writing the understated age and forgot to change it back when re-scribing his poetry manuscripts. In either case, the root cause was patriotic. Which of these two explanations is closer to the truth? It is difficult to gather enough information for a proper assessment today. All we can say is that his year of birth is of secondary importance. The most important question is: What contributions had he made to his country and his people during his lifetime? His greatest contributions were the efforts he made to assist in the national revolution led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen and the many classical poems that he wrote in the capacity of “a full poet and a half soldier” (一個詩人, 半個軍人) that were very representative of the classical poetry of his time.

One of Lung See Hok’s deepest longings was to write the history book Yuèjūn Zhì (粵軍誌; lit. Records of the Yue Army) to recount the establishment of the Yue Army and the path of struggle the Yue Army had followed in the course of national revolution. Unfortunately, this project did not materialize and many of his comrades felt sorry about it. According to one of his descendants, the reason that he did not follow through with this project was because a true account of the early history of the Yue Army would expose things that Chiang Kai-shek did not want people to know and in the event that Chiang was angered, many old veterans of the Yue Army could lose their lives as a result. Those who are familiar with the history of the Republic and Chiang’s way of doing things would probably agree without voicing their consensus. However, Lung’s comrade-in-arms Wú Zhàozhōng (吳肇鍾) had expressed a similar view in a specific but implicit manner in a eulogy written in honour of him (originally meant to be a postscript for Lóng Sīhè Xiānshēng Yíshī Jìniànjí but entered by the editor as the first foreword). An excerpt of Wú’s writing can be translated as follows: “Our province Yue was where the [national] revolution was strategized and initiated. The Yue Army indeed served as the backbone of the force that built our nation. Unfortunately, there was the misfit and I too did not stay in the Yue Army until the end. As for the history, organization, and meritorious accomplishments of the Yue Army, all generals and soldiers were indeed great heroes of our time. Every time when [Lung] wanted to write a book about it in honour of his comrades, the world was changing faster and faster, making it hard to survive the day, and he who governed had things thrown into extreme chaos; consequently, the plan was not implemented but the good intention lived on.” Well, if all generals and soldiers of the Yue Army were great heros, why was there a misfit? Obviously, he was hinting at Chiang Kai-shek, who came from a different province. As well, Chiang eventually became the head of the government and he was the one who governed. The phrases “the world was changing faster and faster” (世變益亟), “making it hard to survive the day” (不可終日), and “things thrown into extreme chaos” (顛倒海隅) were there to tell us how much people were terrified and how much the country was turned upside down.

This website only displays information of historical and literary value. It does not discuss modern-day politics, nor does it perform commercial transactions. The copyright of its contents is reserved by Lung Tin Yick (Tin Yick Lung or Lung, Tin Yick if written in conventional English format) with the exception of the photos in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (courtesy of the Buddhist Triple Wisdom Hall). The manuscripts of Lung See Hok are cultural heritage and should be appreciated as such rather than evaluated on the basis on today’s ideological fashions or political values. Any interpretation, analysis, or quotation made by the readers regarding the contents of this website will not represent the position or opinion of the webmaster or any individual who has supplied information to this website.

| |

| |

| |

| |

英文簡介 - 初載日期:2022-04-26;更新日期:2025-11-01(多加兩個內部網絡連結。)

Introduction - Date of Initial Upload: 2022-04-26; Date of Last Update: 2025-11-01 (Added two more internal weblinks to the page.)